Balancing Quantity, Price, and Structure in the Upper C-Band

The FCC’s Upper C-Band NPRM appears straightforward—unlocking 100 to 180 MHz. Yet the consequences of that range diverge sharply: incremental for terrestrial networks, but structural for satellite incumbents. That gap is what drives pricing, incentives, and strategic choices going forward.

In a recent Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM), the Federal Communications Commission (FCC or Commission) initiated the process to make between 100 and 180 MHz of the upper C-band (around 3.98–4.20 GHz) available for terrestrial wireless flexible use.[1] This note examines the three central dimensions of that decision: quantity, price, and clearing structure. The core finding is simple: while the quantity is incremental for terrestrial users, it is structural for geostationary (GSO) satellite operators, and the resulting price and structure must adjust to that reality.

Quantity: the central variable

- For the terrestrial wireless industry, the relocation is needed but incremental. Even the 180 MHz upper target is short of the near-term need of 400 MHz to support the next wave of mid-band deployments and the long-term mandate of 800 MHz.[2],[3]

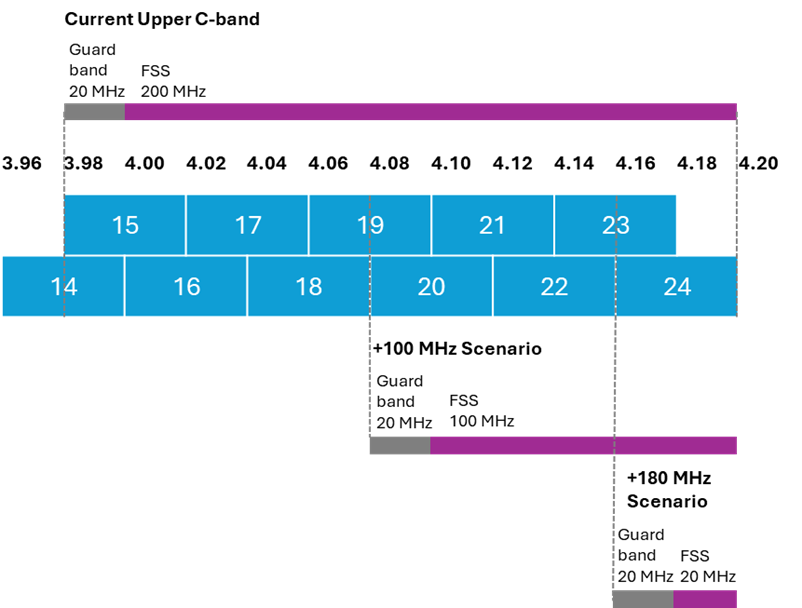

- For the (GSO) satellite industry, the consequences are structural. At 100 MHz, GSOs operators may continue operating at reduced capacity on 5.5 transponders (down from 24 pre-2020). However, at 180 MHz, the satellite industry may have to radically change the way they use the spectrum as only 0.5 transponders (20 MHz + 20 MHz guard band) may be usable by existing GSO C-Band satellites.

Figure 1 shows the implications of each clearing scenario for GSO operators. Currently, the typical GSO satellite operates using 9.5 transponders, but they would need to adjust their operations to 5.5 transponders in the 100 MHz scenario or 0.5 transponders in the 180 MHz scenario – or vacate the band entirely if downscaling proves uneconomical.

Figure 1: Upper C-band clearing scenarios

Price: likely lower than the 2020 C-Band Auction

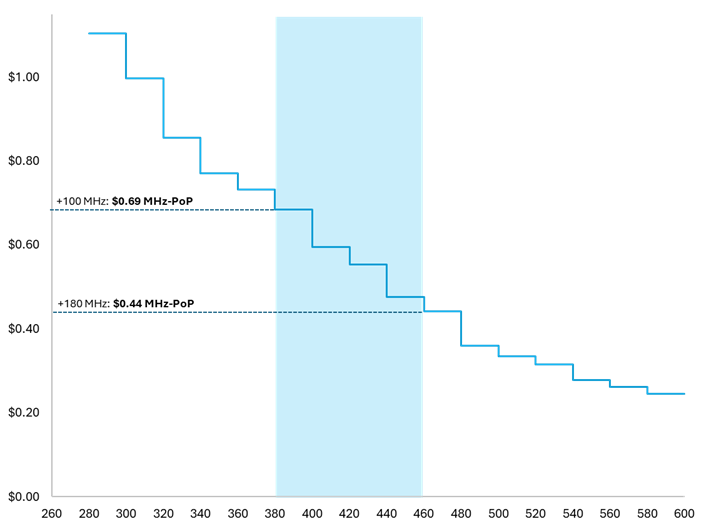

Bidding data from the 2020 C-band reallocation suggests that prices will be lower than the clearing price in 2020. The 2020 C-band auction (Auction 107) cleared 280 MHz at $1.10 MHz-Pop. Were an additional 100 -180 MHz cleared, the price would have fallen to between $0.69 and $0.44 MHz-Pop, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Auction 107 aggregate demand

If nothing had changed, the prices implied by the bidding data would be more representative of the expected price of the Upper C-Band. However, many things that affect spectrum prices have changed between 2020 and 2025: interest rates, inflation, data growth expectations, FWA commercialization, many private transactions (EchoStar sales), increased fiber deployments (the BEAD program), expectations about future spectrum releases, among other factors.

Structure: likely the same, with a tweak

Incumbent GSO satellite companies have signaled that they would favor the structure and incentives used in the first clearing. In the C-band clearing, incumbent operators would receive Accelerated Relocation Payments (ARP) if they cleared the spectrum following an accelerated timeline. Winning bidders would pay their bids, Relocation Costs (RC), and ARPs.

In 2020, terrestrial wireless operators expected to pay approximately $94.87 billion, comprised of $80.9 billion in gross bids plus an additional $9.7 billion in ARPs and around $4.2 billion in RCs – or an all-in price of $1.10 MHz-Pop. A scaled down version of this structure would imply payments for incumbents of between $2.15 and $2.49 billion. Table 1 shows the application of the C-band relocation structure to the Upper C-band – that is ARPs represent 10.22% of the total value.

Table 1 Upper C-Band prices implied by Auction 107 bidding

|

MHz |

Gross Bids (B) |

ARP (B) |

RC (B) |

Total (B) |

Price MHz-Pop |

|

280 |

$

80.92 |

$

9.70 |

$

4.25 |

$ 94.87 |

$ 1.10 |

|

+100 |

$

17.92 |

$

2.15 |

$

0.94 |

$ 21.01 |

$ 0.69 |

|

+180 |

$

20.80 |

$

2.49 |

$

1.09 |

$ 24.39 |

$ 0.44 |

As a general structure, using ARPs to incentivize incumbents to clear the spectrum quickly has proven effective to transition the spectrum. However, it is unclear whether the incumbents will be willing to accept the same [expected] percentage, or equivalent MHz-Pop price, for all quantities from 100 to 180 MHz owing to the structural nature of the larger quantities.

Concluding observations

Three conclusions follow from the analysis:

- Quantity drives everything.

The difference between 100 MHz and 180 MHz is modest for wireless operators but structural for GSO incumbents. - Prices will likely fall below 2020 levels, but the precise magnitude depends on how today’s very different macro and industry conditions influence spectrum demand.

- The 2020 clearing structure is a useful baseline, but the asymmetric impact on incumbents suggests that a simple proportional extension may not be viable for all quantities under consideration.

As the NPRM proceeds, each stakeholder—FCC, incumbent satellite operators, mobile operators, and emerging satellite entrants—will need to anchor their strategy on expectations for both price and clearing quantity. The interaction between these variables will ultimately determine whether the upper C-band transition is incremental or transformative for the industries involved.

[1] In the Matter of Upper C-band (3.98–4.2 GHz), NOTICE OF PROPOSED RULEMAKING, GN Docket No. 25-59, FCC-CIRC-2511-01

[2] https://www.ctia.org/news/the-economic-impact-of-each-additional-100-mhz-of-mid-band-spectrum-for-mobile

[3] One Big Beautiful Bill Act, H.R. 1, § 40002